Take a moment to understand what the word Revolution means etymologically. A “course” of bodies, “revolving” along an appointed path. There must be a central body, exerting gravity, and other smaller bodies, revolving around it. That is what takes place in this first volume of this trilogy, dedicated to the French Revolution. The “immaterial” core is made up by the shattering events of 1789. The smaller bodies are the myriad of characters that we follow, in a complex, kaleidoscopic, varied social portrait of French society in this epochal shift.

As repeated often, revolutions are never monocausal. Florent Grouazel and Younn Locard are not interested in a linear, encyclopedic and pedagogical explanation of the French Revolution. They do use very short typeset texts at the beginning of each chapter, as if we were reading one of the myriad pamphlets being printed at the time in Paris (and which is also explored topically in the narrative). They condense what happens beyond the comics text, which spans months, but above it all, these snippets act as connective tissue between chapters. As we follow this sprawling polyphony of Parisian commoners, sans-culottes, peasant life from the surrounding areas, but also members of the Assembly of all denominations – there are many – and Royalist agents, seesawing between historical figures and fictive characters (sometimes amalgamations of different extant people), we have the opportunity to traverse the echelons of a society on the verge of profound transformation. Moreover, a society quite aware of that, only contributing to further anxiety and turmoil.

Here’s an example of how the book works. A crucial element that lead to the explosiveness of the 14th of July was the dearth and high prices of bread, the most basic staple food. The difference between what commoners could afford and the banquets accessible to high society is not explained via discourses or even a basic episodic contrast. As we simply follow several characters, being one of them a tavern girl, we have the opportunity to see many people dealing with food issues: soldiers stopping for a drink; mailcoach travelers enjoying a meal at an inn; journeymen and -women being denied a cup of wine at the end of their labor; tramps roasting sewer rats; a restaurant owner listing the leftovers of a royal banquet (leftovers which are in themselves a sumptuous meal that will be repurposed for lesser patrons); nobles and businessmen engaged in tipsy discussions about colonial rum, and so on. The episode known as “The Women’s March on Versailles” appears as a clear translation of what we had been witnessing thus far, even if subtly. Eating and drinking and talking about access to food is something recurrent in the book. It is the underlying basso continuo of the actions, a not-that-invisible cause of everything.

This is not a book that will introduce us to the characters, the situations, the developments and the consequences in a didactic way. And it does not present itself as a self-sufficient text, perhaps. What I mean by this is that you have something to gain if you brush up your French Revolution history, so I guess that the more familiar you are with this overall event the more pleasure you will take from the reading of Révolutions. I’m certain that readers very familiar with the events and the city of Paris will fall in awe with recognizing familiar corners as lived in the 18th century, or follow a psychogeographical map of each of the historical steps of the process. The authors provide large vistas of streets, plazas, places, as well as an incredible map of Paris of the time and a wonderful full spread of the fall of the Bastille, so we can revisit those images detached from the narrative as enhanced chronotopes we may engage with for contemporary use.

We will meet familiar names, such as Marat and Robespierre, even if at a distance. But the main characters, if we can say there are some, create a moving geometric trap of our focus. A commoner young woman, called Louise, who finds herself unemployed for protecting her sister’s daughter, a street urchin straight out of Hugo and Dickens. Abel Kervélégan, a fictive twin brother to actual historical figure Augustin, member of the French National Assembly. And others, who crisscross paths over the events and changes of fortune.

Indeed, this book has been described as a fresco, and it is close to the genre of mural painting that shows several discrete scenes that are nonetheless connected in terms of space, actancial roles, and theme. They do not appear as separate vignettes, but scenes with characters whose actions are continuously interweaving with one another so that slowly the overarching narrative becomes apparent. This demands from the reader a capacity to relate each episode to one another. She will be the one providing the necessary inferences that weave the wider context, and instill upon everything the dramatic urgency and the interconnectedness of the “Revolution.”

So, people who are not familiar with it will follow these landscapes too, and by engaging with the broad strokes here, and the little details there, can subsequently attempt to create a framing that will allow for further exploration. A learning that will be rounded off, of course, by the next planned two volumes, Égalité and ou la mort. As you can see, the three volumes’ subtitles make up then the motto printed and presented by the Commune of Paris: “Liberty, equality, brotherhood or death,” which, for American ears, echoes Patrick Henry’s words in Virginia.

Either as a book that you have to read once or twice, or re-read it as you extend parallel readings, it will demand from you an attentive engagement, that asks you to understand what it means to call someone a “huguenot,” “orléaniste,” “bréton,” “jacobins,” even “poissarde,” or other specific, historical terms (again, chronotopic in nature). Read as a roman-fleuve, and epic in stature, this is not light reading, but it puts you in the eye of the hurricane in an outstanding way.

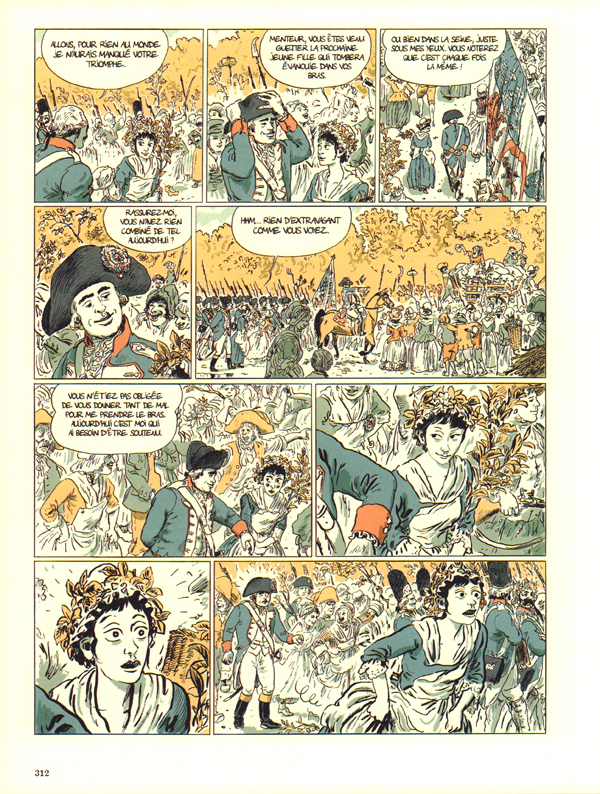

The drawings are superb. They’re wiggly, and fluid, with nervous lines that approach a certain calligraphic nature akin to Joann Sfar and Lewis Trondheim, with a figuration in the middle of anatomical naturalism and cartoonishness. In other words, a pretty typical, solid French-Belgian approach. The page composition and narrational strategies are quite varied. Sometimes we have dense gridded pages filled with dialog, and sometimes we have quick succession of silent panels. There are wonderful spreads and splash pages that could act as genre-paintings by the likes of Delacroix and Géricault in terms of composition. Details abound. When we have long shots of the city, one might as well remain there for a long moment taking in all the little scenes, as if checking a Where’s Wally? Spread. The very limited but alternated palette is wonderfully expressive, and sometimes it feels as if it works as symbolic variations of the tricoleur.

This first volume opens up with the “Affaire Réveillon,” born out of rumors and despair, and then follows a chronological order through the most known episodes, without ever recurring to extratextual captions or that sort of thing. It’s as if the goal is less to explain in macro-terms the events than to convey the actual feelings of all these different people and the contrasting experiences and perspectives in relation to the same events. Opening in an incredible tense moment, when the price of bread was skyrocketing, when political crisis was impeding, and threatening the life of thousands of the poorer citizens, each and every role has a different approach. There are many discussions among the politicians at the Assembly, some of which, the left-wing, are filled with beautiful new ideas of Freedom and the end of so-called “divine” rights of the noble class and, above all, the King… but the people, the commoners, need solutions right now. They cannot wait. And that’s where the explosive action comes from.

Without transforming posterior events or contemporary biases into straitjackets of historical interpretation, one cannot but be remindful of other moments of Parisian resistance and protests, from to the Paris Communes of 1871 (which also has its own comics masterpiece in Jacques Tardi’s adaptation of Jean Vautrin’s novel Le Cri du Peuple – Portuguese only, sorry [also, I have not read, as of yet, Raphaël Meyssan’s Les damnés de la commune]) and May 1968, up to the Yellow Vest movement. And as I write, amidst the Coronavirus crisis, which will be followed by a steep economic crisis that will hit hard much of the working class, how will events mirror those of the mother of all revolutions?

Deixe um comentário