That is to say they become simple vehicles to “tell the story,” to “convey the content”. Their ambition is tied to “what they have to say,” but not to “how they say it.” And before you accuse me of being a formalist prick, let me tell you, that is exactly what I’m being. But not in the simple sense that I do not care for the cultural, social and political significance of any art form, and comics in particular, but in the sense that you have to pay attention to the form too. How you mould the story, how you present it, how you think about panels, and turning the page, and create the lines and distribute the words, must be paramount to create a good work of art, as art.

When I first came across the first results of the Oubapo movement – a comics-related experimental approach that was following the steps of the 1960s literary Oulipo movement – in the mid-1990s, I was enthralled. As a budding writer and a comics teacher, I have been thankful for the “exercises in style” with wich all these authors and thinkers have provided me. But I have always had, at the same time, a strange aftertaste that these are exactly that: mere exercises. They’re fun at a salon, or a spiritied party, but are they actually contributing to an internal transformation of comics as a art form? Are they, as one usually, say, “push the boundaries”? I don’t see experimentalism as much as “going beyond the boundaries,” or “breaking the rules,” but rather as illuminating a previously unknown path of a given territory, revelating thus that the continent was wider than we thought. And it does not necessarily mean that whatever new paths are found have to break into a new genre or mode of working, but simply that they show us something that was already there but never tried before. Without “breaking” or “escaping” the possibility of being called comics… That’s why I have a stronger admiration for, say, Martin Vaughn-James, Richard McGuire or my friend Ilan Manouach than for these little silly but funny games.

Still… Still. Oubapo can o exactly that: shed light into formal possibilities, blossom new approaches hitherto untapped, launch new, well, oblique strategies (to quote Eno and Schmidt).

Elkins, as I mentioned, talks about four proposals. Although it has deep implications, I think that naming them will give you an idea clear enough to proceed: novels “aren’t about real life,” “should not be ‘careful, cautious and professional’,” “need not prove good companionship,” and “is complex.” And graphic novels, or comics in general, can do the same things (can I be a little bit more prescriptive?, they should be?). This means that while we should celebrate the sheer openness with which we have more works, by more people, and diverse people, engaged with current interests and topicalities, making us attuned to the experiences of “other worlds” that we don’t have direct access to, foment empathy and vicarious processes, we should strive for formal excellence, storytelling prowess and open-eyed intent, graphic inventiveness, groundbreaking strategies.

So there should be no problem if, following Elkins, we look for anti-realist work that eschew formulas and dependable structures, and rather provides us with nex texts that acually “fail to give dependable pleasure,” even bringing unease to the reader.

Well, I said “formulas” are eschewed, but actually Oubapo is predicated upon the idea of launching an a priori textual/formal strategy that then is pursued by the artist/creator. As the founders of Oulipo famously put, it’s as if rats put up the labyrinth from which they have to escape afterwards. But these formulas are pushing the creator to come up with a complex solution, so it does not mean the same thing as revisiting familiar and secure structures (3 acts, character development, leit motivs, and so on).

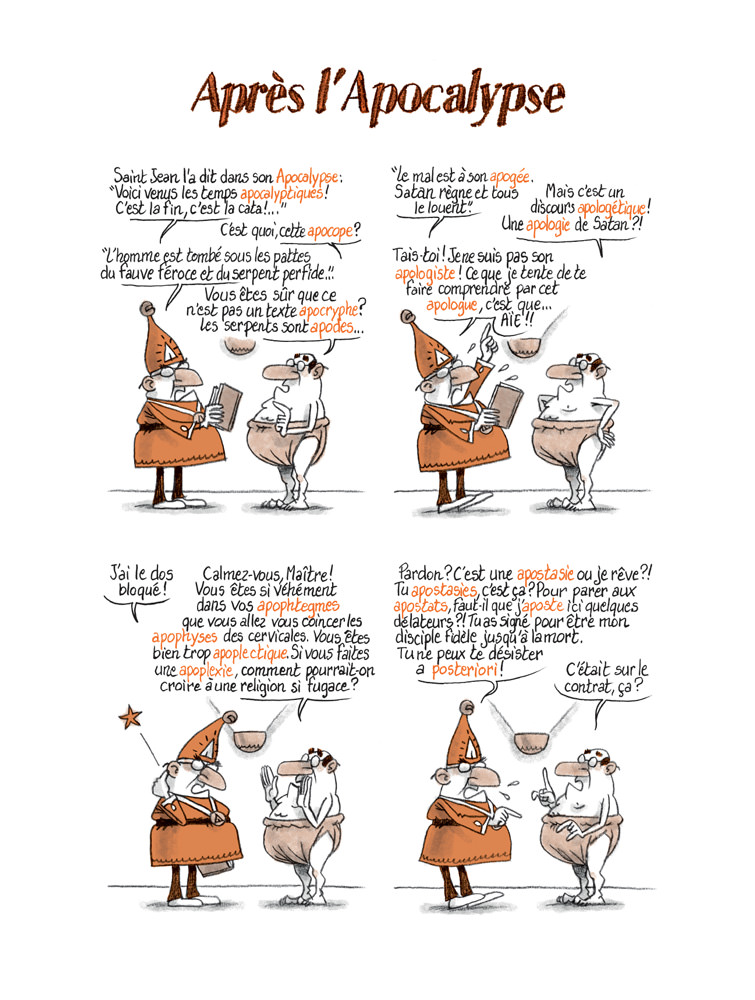

L’Oulipo par la bande is a collection of Oubapo-informed works by Étienne Lécroart, one of the founders and most active members of this movement. The earliest seem to be from 2009 and the most recent from 2020. Many of these pieces, sometimes of a single page or a spread, were created in the bi-weekly meetings of the Oulipo group. All of them seem to have been created on special occasions, and published before in either magazines, periodicals or exhibitions. The book is organized by sections, each of one under the rubric of a process or of figures of speech (rhetoric) that stem directly from the Oulipian menu. So in the first case we have portraits and logo-rallyes, i.e., “rally racing with words.” The first are portraits precisely of key figures of the Oulipo movement, such as Georges Pérec, Marcel Bénabou, “borrowed” member Boris Vian, and others, created with written lines that, with controlled character count, create lines making up their profiles, and two outstanding portraits of Raymond Quenau and Olivier Salon, a mathematician and Oulipo creator. These are amazing because they show geographical maps (say, Paris in the case of Quenau) and then lines that provide a sort of psychogeographical journey through places significant in their life and work. As for the other strategies, we will find the comics application of zeugmas, epicene writing, i.e., using nouns, pronouns and images that are indeterminate in terms of sex, and remember that in French all words are gendered masculine or feminine, and new neutral forms are politically loaded, the “terine” poetic form, acrostics, and so on. The interest and efficiency vary, of course, and sometimes the humour may be either a little dry or somewhat obscure, but that is the premise of Elkins complexity and unease.

These texts are not to be read lightly, and quickly. Sometimes it means work. I can imagine the possibility of, in the future, walking through the streets of Paris following Lécroart’s map. It will be time-consuming, as I will be very close to stage 145 when I am in stage 6, of course, but the point is not expediency, but experience. When reading the logo-rally, which constructs dialogue by placing in natural sentences all the words in a given dictionary, in order, I am not looking for facile entertaiment, or companionship and understanding about “real life”, but rather a radical perspective upon the shape of language, how one chooses to order it, and the transformation in communication thay occurs if we use it as forma material.

So, perhaps less than a book to read, Lécoart’s volume is a “stringent proposal” that, again quoting Elkins, “keeps you wondering, keeps you working to understand what the author thinks they’re doing, and does not ever answer your questions.”

Does that answer your question?

Deixe um comentário