Coché has created a significant body of work with books that create a more or less narrative structure, sometimes with a little text, more often than not without it, with a series of engraved images. On another occasion I have argued, in a silly pun, that these are not “bande dessinées” (drawn comics) but rather “bandes gravés” (engraved, although in this particular case, in English, etched). I have been privileged to have organised a two-part show that included some of his aquatints, and it’s wonderful to be close enough to inspect the subtle work of the shadows and tones of the prints, the seemingly excessive scratches and fine lines across the images, the “unfinished” countours, and so on. Nevertheless, the reproduction of these prints is so fine that you can inspect these subtleties yourself, beyond their mere role as vehicles for representations and readable actions. Coché has also created fully painted books (Hic Sunt Leones and L’homme armée), which despite creating similar researches about the coordination of images and meaning, were visually drastically different. L’Almageste, even thanks to its format (a square measuring 31 x 29,30 cm), is a return to form, as it were.

The title Almageste is a clear reference to the ancient treatise on astronomy by Ptolemy, in which a geocentric geometry of the movement of the bodies in the firmament was established and would preside over both Western and Eastern imaginaries for centuries, until the Copernic Revolution. The word itself is the result of a complicated history of trans-linguistic distortions across centuries, so that the original title in Ancient Greek – Hé Mathématiké Syntaxis, “A Mathematical Composition”, but which could also be understood as “ordering” or “arrangement” (syntaxis) of “astronomy”, “knowledge”, “science” (mathematike) – would end in the Arab word al-majisti, “The Greatest.” However, I also wonder if there is not here a possibility, on the part of Coché, of an thematical influence from another Arab word, also quite influential to the history of book-making, printing, and scientific or knowledge divulgation: the almanach, from the Andalousian Arab al-manak, translatable as “a moment in time” or “stage.”

Indeed, if we read the book in a certain way, we will come to understand how every single action we see implies its corresponding consequence, and reaction, so that causality, no matter how phantasmagoric and feeble the narrative coordiantion may look like in a first read, becomes the force that animates the events of the book. Moreover, Coché seems to investigate a sort of Apocalypse. Which is, after all, precisely a “stage” in the history of Humankind, one of future upheaval and destruction. At least, of great change. And change is what we witness throughout these pages.

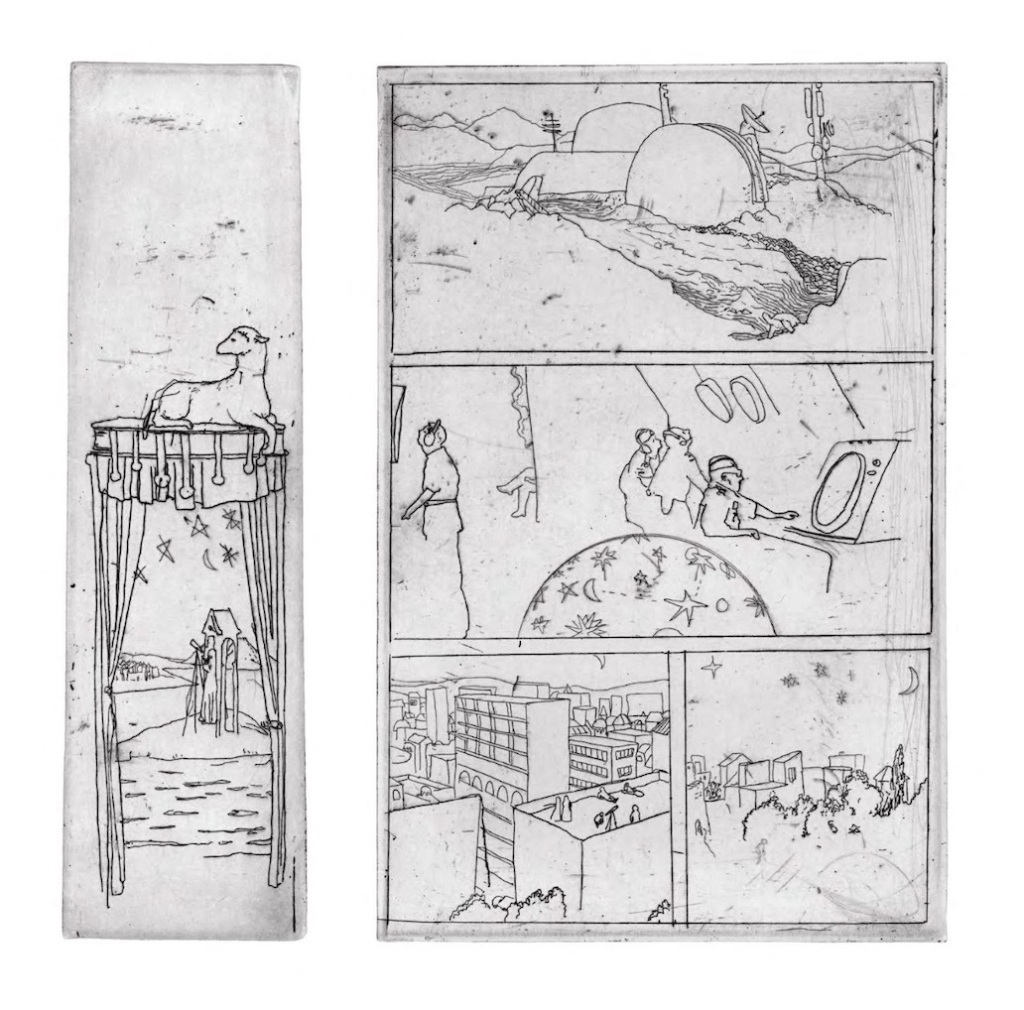

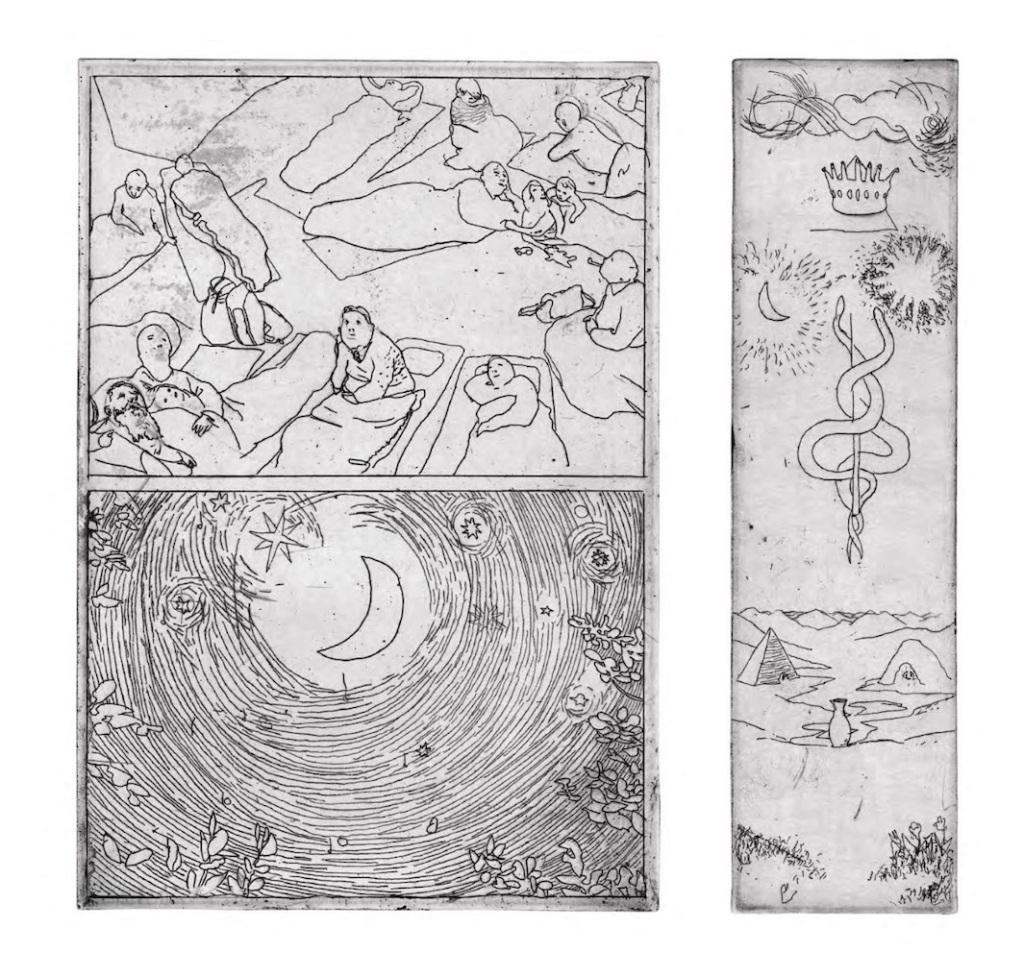

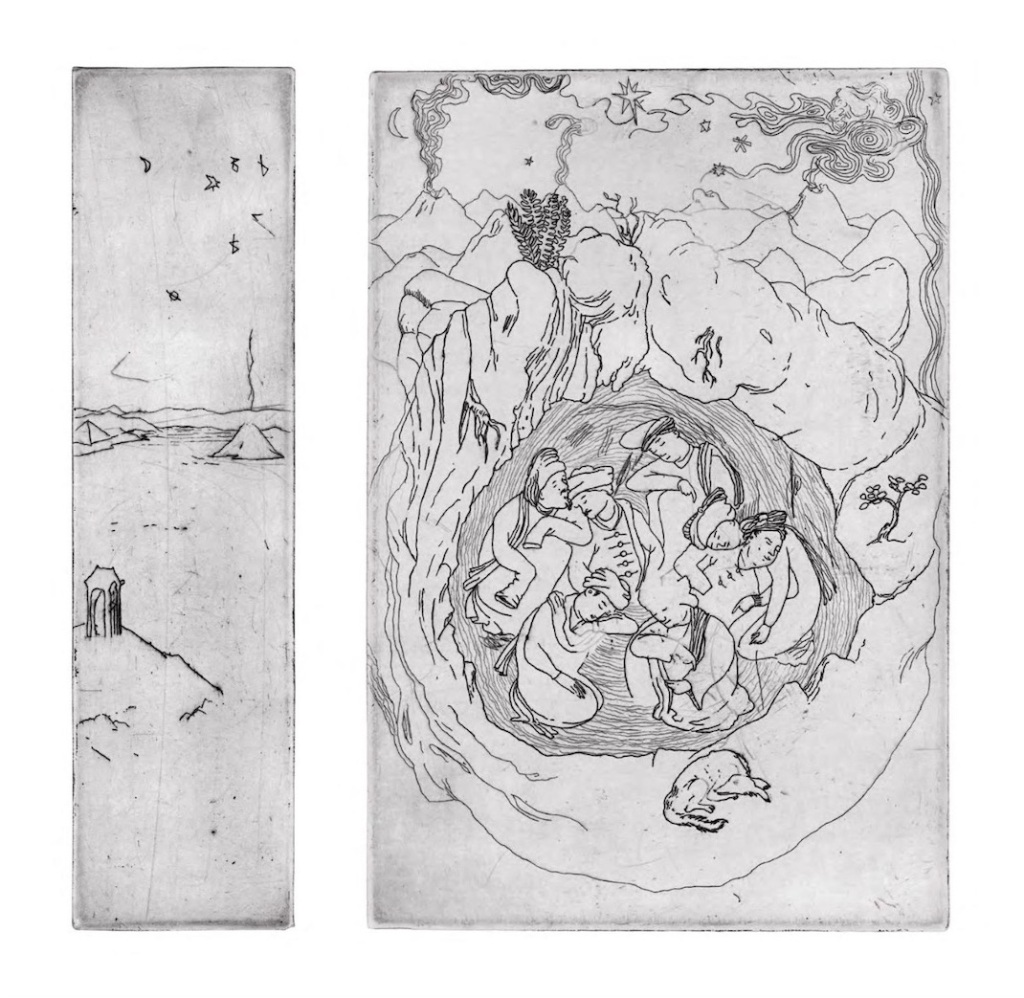

As is usual in Coché’s work, the narrative flows through a sequence of images without verbal aids, but in which intertextuality or intervisuality is always strongly present. I have discussed elsewhere how an older book, Hortus Sanitatus, plays with a more or less specific (Belgian) visual cultural memory in order to isolate elements with which the author then weaves back a storyline. The same things happens here. One can almost create a list of sources for each and every image – panels, that is, some of which are etched into one plane of composition, others are combined, etc.; the page composition of this book is done in post-production, as they are clearly photos or scans of separate etchings, in the most diverse formats, arranged into a singular page. These pages are arranged in such a manner that we can say to have at the center a “main story”, more or less sequential in a classical manner, whereas at the margins we have “side notes,” or “side scenes,” that present other realms of action. Also, many of the actions, when they are being shown, are interrupted briefly by an image that seems a little more symbolic, which may be a more or less direct, more or less oblique commentary about the even we’re just witnessing, as if opening it up to broader interpretations.

As for the sources, you may identify Christian Middle Ages paintings, and illuminations, but also Persian miniatures, all sorts of magical, astrological or esoteric material, not to mention representations of modern landscapes and technologies. Despite its more central Medieval roots, this Apocalypse also employs imageries that stem from more modern sensibilities, from zombie to kaiju films. All this jumble allows us to imagine a synopsis that makes L’Almageste‘s point of departure at some point in our recent history, where people are forced to camp outside – it is a catastrophe brought from the stars, or something more prosaic, like a pandemic, but that nevertheless is reflected by the stars and portents in the night sky? – to die and be born again. Whatever the reasoning, humans are dead, but their skeleton-dressed spirits arise and try to recreate a new society, in a deeper harmony with the cycles of nature. L’Almageste is, undoubtedly, a narrative of rebirth and relaunch, of a hope in a child’s-like glee life if we are willing to let go of all the accoutrements and niceties of our modern quotidian, too boged-down by material necessities. So death, destruction and the anihilation of the system of the world is not see as a tempestuous, terrible, scary thing but rather as an opportunity to return to the playground that has been promised us.

There’s a number of paralell scenes that seem to create thematical threads: a turtle hatching from its egg and searching for its way; a bearded monk observing the skies and taking notes; a pair of skeletons watching a movie of a terribe war between an army and a giant spider; several hermetic acts, including the harvesting of hearts, and so on. These contribute, in one way or another, to the accumulation of meaning that makes up the critical mass of the entire project.

Frédéric Coché is always able to pilfer from so many sources in a coherent way, informed as he is by contemporary practices of meaning-making. Whereas one could think of films such as Sergei Parajanov’s or Alejandro Jodorowsky’, in which enduring visual compositions are more powerful than a subsumption to heteronarrative structures, one could also argue that in some moments Coché simplifies the episodes under the guise of more familiar, and therefore domesticated, strategies. For instance, the episode of the angel defeating the dragon and then the Melusine-like character might as well be part of a number of high fantasy graphic novels. Even the figuration seems to follow simpler, ligne claire directives (I guarantee you, there are clins d’oeil to Tintin and Moebius).

Then again, the author has always played with tropes in order to, paradoxically, subvert and celebrate them.

Deixe um comentário