Francisco Sousa Lobo’s intense output has made him put out multiple volumes in the last few years, almost all of which in English (with Portuguese translations in footnote form), and all of them interlinked by a common strategy. While I have written extensively about his work in Portuguese (starting with The Dying Draughtsman to The Care of Birds, but also paying attention to smaller work) and, on one occasion, in English, it is strangely appropriate to write about this volume, which only exists in Portuguese, in a foreign language.

We can describe Lobo’s overall project as a sort of dislocated autobiographical project. His books are not necessarily or classically autobiographical, although he has a number of projects that fall squarely into that category. But they’re not self-fiction either as, say, Eddie Campbell’s Alec books. Sometimes he uses his own name and likeness for the protagonists, some others he uses very different characters but that share with him any given trait, that may or may not be carried onto another title. In any case, his books can – perhaps I would even go as far as writing that they should – be read together, as in an ongoing series of interlocked texts or pieces in a fragmented puzzle. Somewhat like Edmond Baudoin’s oeuvre, in which each step reaffirms or rewrites the previous ones.

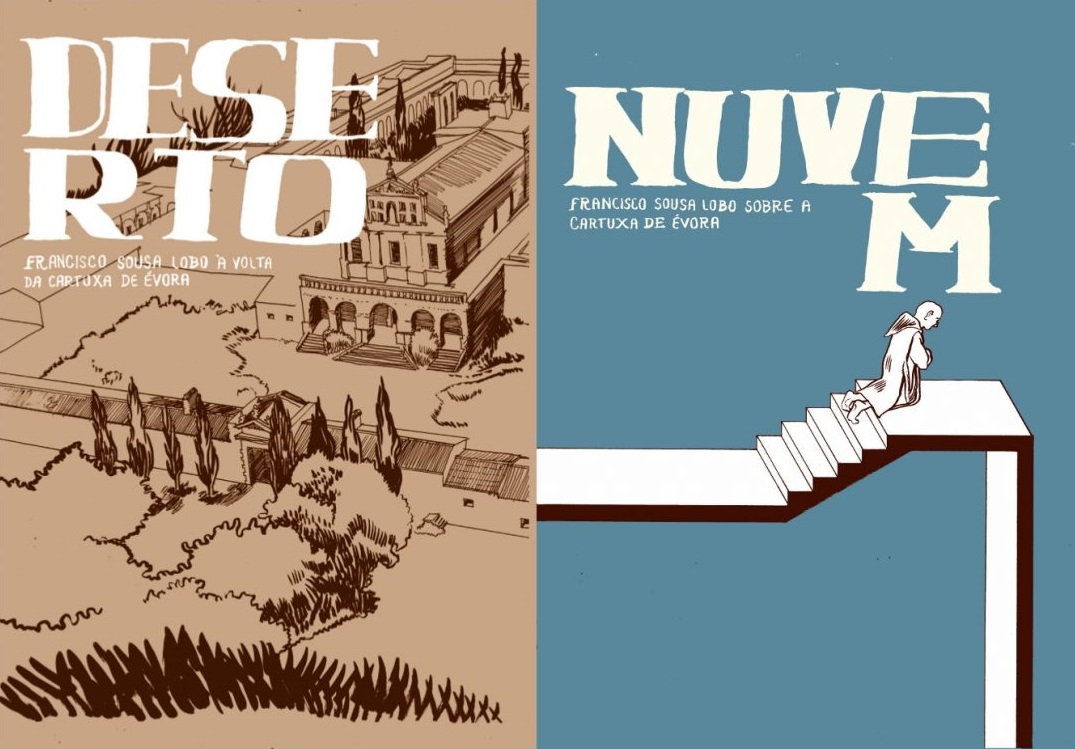

This book is called, in English, Desert/Cloud. Bound dos-à-dos, you can either begin on the one end (or book) or the other. The interchanges of Lobo’s book, or books, become particularly and literally strong here, then. There is a natural common core, but they are very disparate texts, in both structure and dynamics.

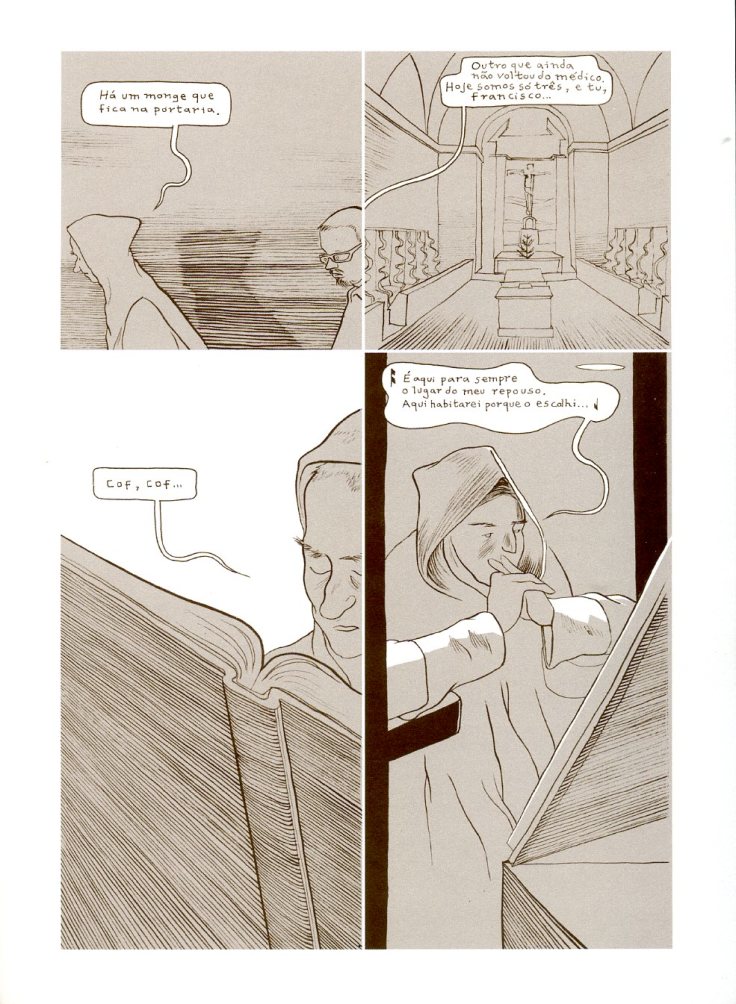

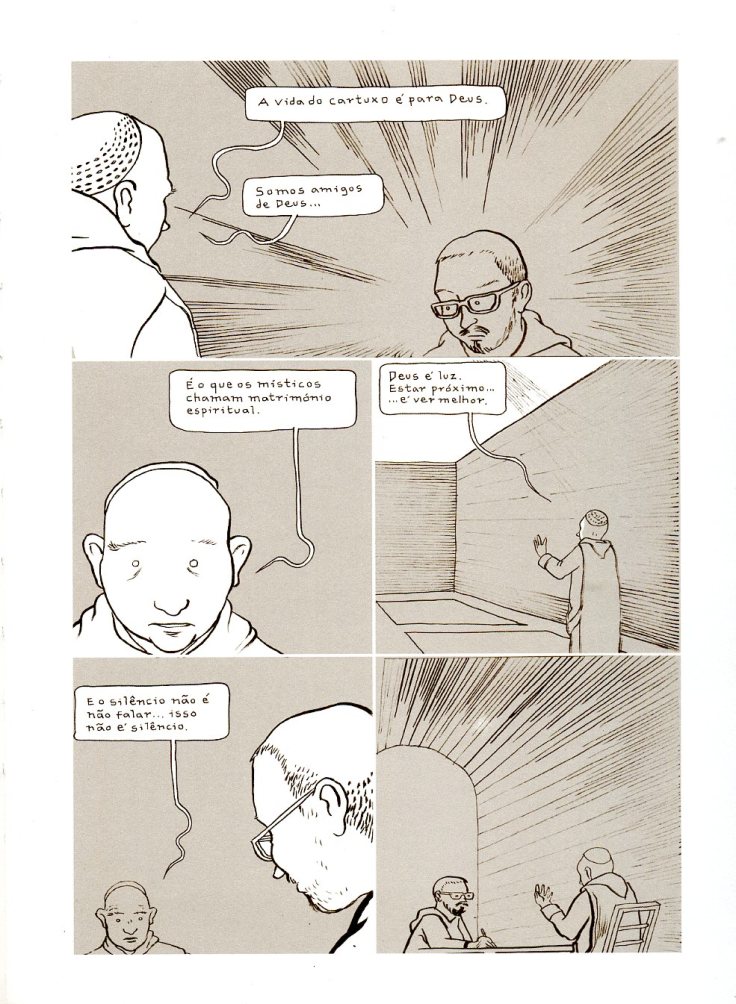

Deserto can be seen as following a more or less straightforward autobiographic mode, about the many visits Francisco has done to the Santa Maria Scala Coeli, the Cartuxa Carthusian Monastery in Évora, Portugal, less than 90 miles to the Southeast of Lisbon. Drawn in very fine lines with some grey swaths, this follows a rather conventional-to-rhetoric page composition, as most of the scenes want to represent actual actions that took place with the protagonist. We follow Francisco arriving at the monastery, following the monks in their daily chores and prayers, discussing theology with them, and trying to understand notions such as silence, isolation, Love of God, and the role of spirituality in a contemporary, cynical world, a world of which Francisco Sousa Lobo is not only a part of but also an actual contributor. That is to say, to a certain extent, the very project of constructing a comic about this experience – sometimes after a more or less experimental, performance fashion – may be what distances him inexorably of the potentiality of a truthful, spiritual experience. Despite the narrative structure being more or less organized around the events told in a chronological manner, there is no single train of thought but a series of smaller train wrecks as Francisco blunders through the corridors, and talks with the monks and other people… His character’s lack of confidence and sometimes overtly obsequious manner defeats him at every turn.

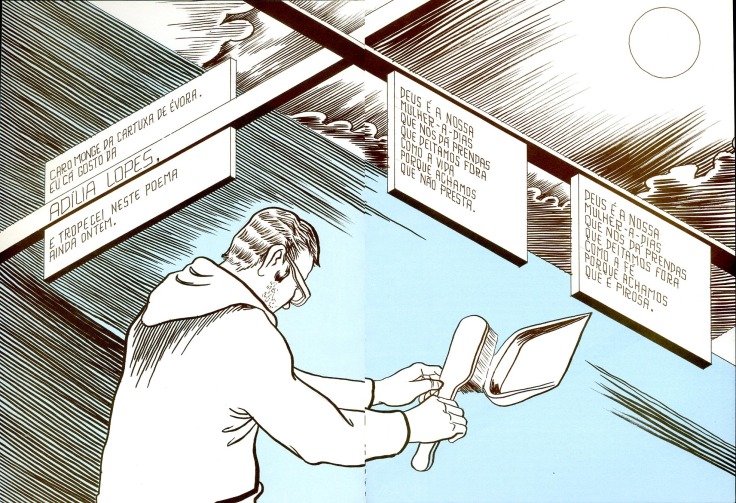

Nuvem follows rather an epistolary mode. Presented as a series of short letters, with images that usually stretch across spreads, each turn of the page reveals a sort of small unit of concept, where a thought, a theme or an image congeal into a significant topic. With a title page and then two spreads, each “chapter” or “letter” emphasizes an aspect of monastic life, from its rules to the order’s history, from the building’s plant to more abstract ideas that attempt an understanding of God. As a Catholic, Lobo has been exploring religion for a long time. Whether in his auto-fictive novels or even adaptations (his participation in the small Portuguese publisher Ao Norte’s series of cinema adaptation into comics, “The Film of my Life”, was, perhaps unsurprisingly, an adroit representation of Carl Dreyer’s Ordet), his complicated bouts with Catholicism become a tug-of-war with his deepest obsessions, returning fears and maladroitness with the modern world. Nuvem/Deserto just makes it clear enough, not only through Francisco’s direct confrontation with the monks as with the readings he makes of the Church’s Fathers, of Kierkegaard or of Simone Weil.

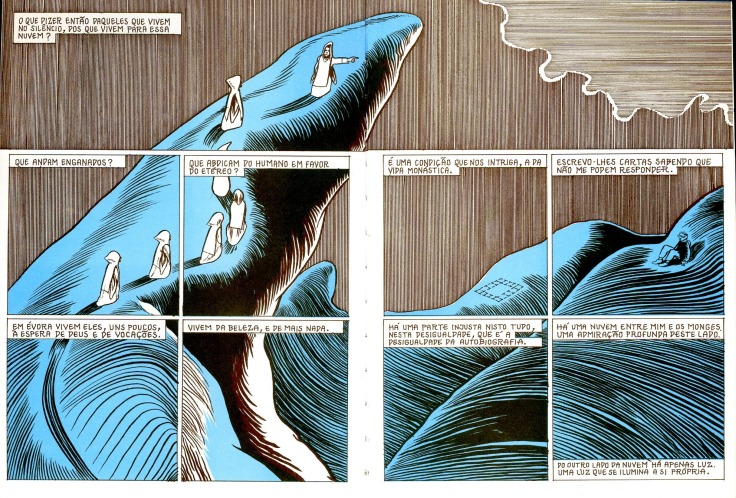

If Deserto shows us an autobiographical external event, Lobo’s visit to the Évora monastery, Nuvem reveals other more internal concerns, but one complements the other. On the one hand, we learn more about the origins of Catholic monastic orders, their importance in the development of the Church, of Christianity but also of the societies and cultures they spearheaded, and on the other we try to come to terms about their role within the contemporary world, as well as of the spirituality that they uphold.

There is this typically post-modern feeling that we are living in disenchanted times. Political utopias don’t work anymore, simplistic narrative structures fall apart, there’s not even one center to be considered. Nanni Moretti, in Palombella Rossa, asked himself what did it mean to be a Communist at the end of the 20th century. Lobo is asking “what does it mean to have faith in a secular, post-digital, post-art, society?”

There are no external comparisons with other faiths, but a culturally grounded dialog with the History of the Church. It is easy to dismiss cynically Catholicism as a set of repetitive, ritualistic behaviors with no strong connection with spiritual matters. Lobo considers many of the arguments and reasons presented to point out a preference for a life within the material, secular world, but, one by one, tries to comprehend the choice of the monks to be apart from such a world, without however, being able to become a part of that same community. Indeed, his discussions reveal that this approach to faith, religion, and dogma is done with intellectual prowess. We are not solely within the domain of piety. I do not want to say that there is a gnostic dimension to the books, but Lobo quotes from diverse sources, as I’ve pointed out. Through them, and around them, not only he engages in complicated philosophical debates, or thematizes verbally their ideas, as he also draws from them the different strengths that can still be tapped into in order to become very close to a certain “truth” or “purity” of pious feelings, which are then transportable and amenable with daily life in the big cosmopolitan city.

It’s as if Sousa Lobo is attempting to demonstrate how the comics form is amenable to be used for the creation of “spiritual exercices”, in its original Ignatius Loyola sense. A form of concentration and meditation, of drawing up a cartography of thought and experience, of interrogation of oneself and the world. As in most of his work, Francisco Sousa Lobo explores many different forms of organizing the panels throughout the pages, at one time playing upon classic page composition structures (the grids) and open-ended dynamics that complicate diegetic and non-diegetic spaces. As in the example I show here, the author shows himself within the landscape that is crossed by the monks, as if acknowledging his will to partake of the monkis world but at the same time revealing how distant he is from them. In one of the panels, one can read, “I write them letters knowing that they cannot write me back.” He also uses often depictions of what look like monumental architectures, a sort of imaginary installation, building-sculptures, exhibition spaces with their objects, but that act at the same time as diagrammatic structures for the comics-specificity expression of moments, ideas or actions. This is especially true in the Nuvem side of the book.

Another recurrent visual trait of his work is the creation of austere structures of very fine hatching, wither parallel or radiating lines, that center objects within a plane, isolate a character or highlight an emotion. But this has always to do with thematic characteristics as well, and if one associates these strategies with previous projects, and Lobo’s depiction of issues such as mental health, paranoia, and Messiah complexes, perhaps one will isolate episodes within this autobiography that underline Francisco’s bouts of these problems within the framework of a clearly tensional relationship with God. In one scene, when Francisco is listening to the superior of the monastery, he does not utter a word, but both the first and the last panel show him at the center of the departing, radiating lines, as if it was an aureola, making him the subject of both the grace of the moment and the benediction of the spoken words. So while visually speaking many of Lobo’s mannerisms are present, in this context they explore the emotional, perceptive and, I would dare say, mystical impressions of his experiences.

Comics making as a form of prayer?

Deixe um comentário