Twelve-cent Archie is the first volume of Rutgers University Press’ “Comics Culture” series, edited by Corey Creekmur, which in its first 5 volumes has already, unsurprisingly, carved an important niche within English-language comics scholarship. Bart Beaty’s volume, however, is a very peculiar case, not only for the continuous brilliance of Beaty’s individual contributions but the frisky freshness of the style in this book.

To a certain extent, one may read this volume not only as a project on Archie comics, specifically the ones around the gang of the red-haired all-American character – the publisher and its editorial practices and policies, the artfulness (or lack thereof) of the involved artists, the paradoxical simple-complex diegesis of its characters, and the way it bungled through the social themes of its time – but also as a comment on the state of comics scholarship itself. As the author writes right off the bat, “auteurism has been the key to the cultural legitimacy of comic books, and it is no surprise that scholars trained in a literary tradition that is so strongly structured around an auteurist canon would transpose that tradition onto comics,” an attitude that leads to a particular “cultural cherry-picking” among an incredibly varied and immense field that “has left enormous gaps in both the history and cultural analysis of comics” (pg. 5). Archie comics, then, with their “low cultural cachet,” may provide a different take on its social portrait.

With that in mind, Beaty did not choose the “best” Archie comics, as he makes clear, but rather “I have focused much more closely on the ‘typical’ Archies” (186). For that, he selected a very precise interval of its production, from December 1961 to July 1969, when the titles (Archie, Pep, Betty & Veronica, Reggie and Me, Life with Archie, and so on) raised their cover price from ten to twelve cents until they were pushed to fifteeen cents, hence the book’s title. Although there are many other factors involved in this choice, that are discussed throughout the project, Beaty sustains that “[t]his seven-a-half-year period corresponds with the peak years of the comic’s production” (7).

The book is constructed after a very different fashion from most scholarship books. First of all, the chapters, exactly a hundred of them, are quite short (some of which one single page long) and zero in on very specific points, whether an abstract notion (say, race) or a character’s hairdo, from a particular author’s signature move to the role of a minor character, discussing either sweeping generalizations about the whole “twelve cent” era or the minutiae of a particular 4-page story. There is no straightforward bibliography, although Beaty does address now and then issues that have been discussed elsewhere (by him or other researchers). There are no footnotes to corroborate his arguments (well, there’s one). And there is not one single disciplinary approach, as all these foci ask for different takes and discursive strategies.

And then there’s a humongous streak of irony through and through. It is very difficult not to chuckle in most of the chapters when Beaty takes a stab at a myriad of targets: Archie comics’ morality, uncritical fannish consumption, and even, why not?, comics scholarship itself. Some of the treatments are hilarious – like the use of mathematical economics to solve the vexing question on the Archie-Betty-Veronica love triangle, or the issue of typos in the comics, or value judgments about everything really, in an opinionated, acerb and ultimately funny mode. They all impart nonetheless, a resolutely incisive interpretation not only of this series as well as the world around it.

This does not mean that Beaty does not tackle hard questions, such as ethnic representation, the role of female characters and feminist perspectives, sexual mores, juvenile delinquency, capitalism, issues such as social ascension and class, and so on, revealing cringe-worthy stories that are the more shocking for delving into such subject matters in a way that seems “natural” within its very social world. The author finds a “preracial, presexual, and postlabor framework of nostalgia” (82) presiding over the fictional world of Riverdale, a town which “could be any place” (30, emphasis added), which also mirrors the traits of the characters, reduced to a small number of characteristics which turn them less into full-fledged and -fleshed characters than ready-to-deploy ciphers. Furthermore, that seems to be the crux of the matter, as what Archie ultimately reveals is the “central paradox of the privileged middle class. Stories do not begin from a flaw in Archie’s character but are situational” (18).

Beaty quotes Umberto Eco’s famous essay “The Myth of Superman” to speak of what seems to be an important attribute of the Archie comics production of the era. Each title would carry a varied number of stories, and seldom issue-long stories. But above all, and in conformity with other practices in comic books-making in the U.S., stories had no “continuity,” which would allow for authors to reset the “Archie universe” in all stories. In a nutshell, “story logics are circumstantial, and they stem from the collision of characters that retain a roughly fixed form with an endlessly generative series of new story prompts that can be infinitely recycled until they have been exhausted of comic potential” (21). So sometimes Veronica is an artful skier or cook, and other times she has no idea of how even to begin any of those tasks. Any given character may have a dog that will never be referred to again. Professional backstories of the adult characters seems to wobble from story to story. Hairstyles appear and vanish lackadaisically. In other words, coherence is less important than the availability of a few general traits that allows authors to rehash and tweaking them according to the needs of the present project. However, the formulaic quality of many of the stories is not simply knocked down by Beaty but understood and pondered upon as their very formal nature, inviting one to consider them as themes and variations that may reveal something beautiful and engaging. The author adds, that “[i]t was when the Archie stories were stripped down to the sparest of elements that they were best able to shine” (195). This forces us to rethink the categories with which we analytically read comics, lest we also start to explore the same things over and over again, and become stale.

Despite the criticism Beaty draws on auteurist approaches to comics, he does not dispense with emphasizing some of the most effective work by top-class artists, so it should come as no surprise that Bob Montana, Harry Lucey, Samm Schwartz, Dan DeCarlo, and, thanks to his short run with Little Archie, the intriguing Bob Bolling, some of which have their own small chapters. Beaty analyzes carefully and in detail what makes each one of them household names not only in the series but in comics-making in general, as he provides close readings of the visual, textual or composition strategies that turn them into masters of visual storytelling. Many of these readings are master classes of close analysis, as one expects.

Finally, the small personal anedoctes he shares with his audience makes Twelve cent Archie also, at times, a moving reading, as it opens up questions on reception and the secret origins of scholarship. An object-lesson in itself, Bart Beaty’s latest book is a breakthrough in talking about comics.

***

Pedro Moura: Let’s start with a basic, even ridiculous question, but one that nonetheless must be asked. Why Archie? You argue that you were looking for an example that went against the grain of most comics-related celebratory discourses (whether academic, journalistic or fannish), something with a low “cultural cachet.” What made you choose Archie over other possibilities (of which there are many examples to choose from, I’m sure)? How important were your personal memories about reading Archie, that you discuss in the end of the volume, for the project?

Bart Beaty: I wanted to write a book about a series that had a wide readership but which was one that I hadn’t personally read for decades. I think that my three primary choices were Archie, Richie Rich, and Mad Magazine. All of these were humor magazines that I had read at a very young age but never returned to as an adult. In that way they were distinct from more celebrated comics like the work of Carl Barks, which I read as a child and have read several times as an adult. Ultimately I determined that Mad was probably too celebrated for what I wanted to do – and, to be fair, there is a lot of good writing on Mad. I opted against Richie Rich because I thought it might be too repetitive for what I wanted to do, although now, of course, there is a part of me that thinks “Hmm, a book on Richie Rich would be great!”

PM: Your analytical focus is exclusively on what you call the “twelve-cent period,” which takes most of the decade of the 1960s. You explain thoroughly the reasoning for this, within a larger output, as the character appeared in 1942 and is still around today with new material. Apart from the rationalization for this that you explain in the book, how definitional was this time period in the shaping of the characters, the art styles, and the series’ social perception and reception?

BB: There is a certain arbitrariness to the choice. It became very clear right away that I couldn’t cover seventy-five years of comics in a single book, so I knew I would have to curtail that. My first instinct was to begin not at the beginning but at the creation of the Comics Code, since John Goldwater was so involved with that and Archie represented a certain kind of Code-approvable title. I anticipated ending in the early-1970s, really with the creation of the television show Happy Days, which is a sort of gloss (I think) on Archie. As I worked on the project, though, the further narrowing just came to seem like a good idea. Plus, the focus on the twelve-cent period meant that I didn’t really have to make an argument about where to begin or end, it was something that was done for me.

That said, I didn’t read much of the ten-cent period that precedes my book, nor the fifteen-cent period that comes after it until the book was sent to the publisher. It was only then that I read the material, particularly in the flagship Archie title. I wound up buying all of the fifteen-cent Archies drawn by Harry Lucey up to the point that he had to retire because I genuinely enjoyed them, and I also moved backward into the 1950s to get the earlier Lucey stories. I’ve come to believe that the twelve-cent period really does crystallize the Archie house style. You can see as they moved into the 1970s how Dan DeCarlo’s visualizations of the characters is a stronger influence on the next generation of artists than is Lucey or Samm Schwartz, and there is a real gelling of the line. There are important changes in the fifteen-cent period – the addition of Chuck is a real notable one and important one, but also the fleshing out of the Betty-Veronica-Archie love-triangle as a genuine conflict. I think that if I had decided to expand the focus of the book it would have been more fruitful to take in the 1970s than the 1950s.

PM: At specific passages of your book, you seem to disparage the very comics series you’re studying, such as when considering it a tad “one-note” or when writing, “[t]he punch line is obvious and unsubtle in perfect keeping with the logic of an Archie comic.” Would you consider that it is this sort of zero degree of comics storytelling but that nevertheless makes up its charm and long-standing life in the imagination? How different are the narrative mechanics of Archie in relation to, say, Disney, Harvey or Little Lulu comics (these, admittedly, aimed at a different readership in terms of age)?

BB: I was always very cognizant of the fact that I was writing a book about comics that I didn’t really care that much about, or didn’t think that I cared about. I do find that an awful lot of writing about comics is very celebratory and I understand that. People choose to work on long projects because they have an interest in the material. I think that the idea of writing a book about something that they don’t like would terrify a lot of scholars, to wake up in the morning and have to work on something that they find unpleasant. So I definitely get that. I was definitely hoping to learn something about Archie comics when I did this book, though. I genuinely did not know what I was going to find. There was a huge part of me that feared that there would be no book here once I actually started the reading, and the possibility of failure was palpable for a long time.

What I did find, though, is touched on in your question. There is, in fact, a form of story-telling here that is quite appealing. The very slight story with one-dimensional characters that allows gags to unfold is quite interesting to me. I’ve had the opportunity to speak with a number of creators who work with Archie now or have worked with them in recent years and we always end up talking about why the comics were so much more popular in the 1960s than they are today, and I always point them to the slight stories and lack of continuity as part of the charm that has been surrendered now that continuity is so much more central to comic book storytelling. I very much admire the work of Don Rosa, for example, but I always cringe a bit at his attempts to construct a logical continuity in the Barks stories – I just don’t think it’s necessary. The more I read children’s comics from the fifties and sixties, the more I realize how at odds they are with contemporary children’s comics that are less popular, even when those comics are well made.

PM: Would you say that Archie’s social universe is more conservative by seeming not to deal directly with current affairs (feminism, civil rights, war, social unrest, etc.) than other works that may have addressed them explicitly even if to provide a conservative view? It seems that by not representing non-Anglo white characters, by downplaying female empowerment, by showing how Archie could never be a juvenile delinquent, and so on, but through ostensibly anodyne stories, its hegemonic power becomes even more powerful, presented as “common sense”.

BB: Yes, I think that’s true. Recently a 1970s Archie panel dealing with feminist issues (women’s liberation issues, to be historically precise) was circulating on social media. It was out of context, just a single panel. A number of people sent it to me hoping that I would be able to identify it, and I think every reader was struck by the eruption of social consciousness into Archie (they were all also disappointed by the actual story). Some people even suggested that it must be a fake [ed. note: through the Comics Scholars List, I’ve learned that a member of the Fans of Archie Comics Facebook page identified it as being from Life With Archie # 147, dated 1974].

Archie comics had remarkably little social imagination. To be fair, it’s not like the rest of the comics industry was much better. The entire industry moved very slowly, despite the fact that there were artists who wanted to tell more relevant stories and expand the social world. Again, Chuck arrives quite late on the scene, but one good thing about that is at least we are spared the spectacle of a character like Ebony White in The Spirit. To be fair to the company, they did eventually take a stronger leadership role on LGBTQ issues with Kevin Keller, which was a risk that they should be applauded for taking.

PM: A very interesting point you make is that Archie’s stories, in the main, have no continuity. You write, “If the Archie comics are a story-generating machine, one important element to note is that it is a machine that can be endlessly reset” (pgs. 20-21). This has repercussions on the character’s abilities, memories about past stories, events and relationships and sometimes even their physical appearance. But do you feel that “continuity” in itself is seen as a desirable trait in the contemporary cultural appraisal of comics, as a sort of “maturity” sign of the medium, which Archie would lack? Do you think that this is part of the problem: evaluating one kind of work by the characteristics of another?

BB: Yes, it’s clear to me that Archie Comics, as a company, is committed to proving the maturity of their line by bringing it into the norms of the industry as a whole. And certainly the Riverdale tv show does that as well.

Continuity came to be seen as “mature” in comics because it allowed characters to change over time. Peter Parker became a more nuanced character as he learned from his mistakes, moved from highschool to college, and, particularly, after the death of Gwen. You couldn’t have that kind of psychological arc in Archie. The character was always the same at every point in time. Personally, I think continuity is wildly overrated in comics. Indeed, I think it has been one of the narrative elements that has been the least productive in terms of generating interesting stories. The idea of the “serious” genre comic is such a strong talisman, however, I don’t see many creators moving away from it.

PM: There’s a moment when you describe the stories published in Life with Archie as being, at one time, “the most self-consciously literary” and “the worst.” Once again, this seems to address a certain expectation of using certain desirable traits accrued in other types of comics and then turning them into a one-size-fits-all solution for the appreciation of comics. You’re arguing for a more nuanced and focused take on (a more varied corpus of) comics. How does this related to the future broadening of Comics Studies, with comparative takes such as Ian Gordon’s Kid Comic Strips or your own project with Benjamin Woo?

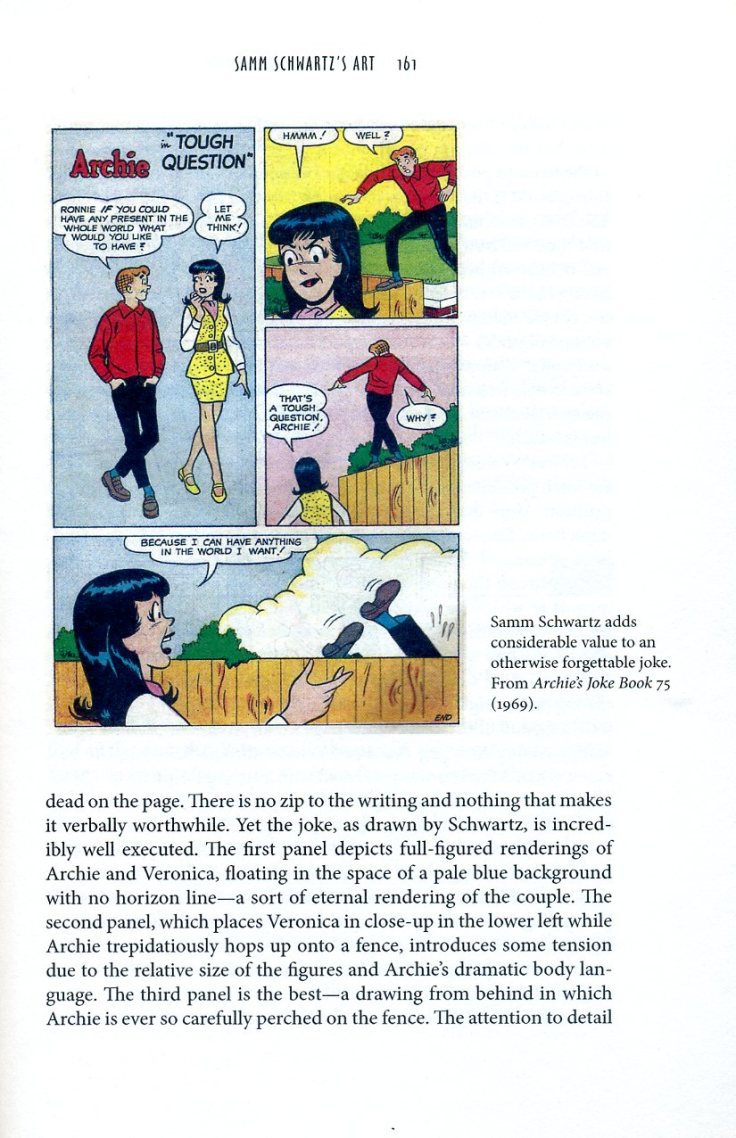

BB: In one of the lectures I do every year in my Introduction to Comics class I use the Samm Schwartz single-page gag that is discussed in the book (pp 160-3) and discuss it at even greater length. I mean, we really go over that page and all the stylistic choices that went into it as a way of talking about what cartoonists do well. In the end, of course, it’s still a really bad joke. It’s just a really bad joke told really, really well. I’m not sure that most aesthetic systems are set up to recognize and value those kinds of contributions. Sadly, not even in comics studies.

The graphic novel tradition in comics studies is very strong at the moment, very much in a period of ascendancy. The good news is that this has led to a lot of very strong scholarly work. The bad news, from my point of view, is that it has occluded so much of comics history of the type that Ian talks about in his (great) book. In the What Were Comics? project we have randomly selected more than 3,000 comics to study. I haven’t read all of these yet – far from it. But what is really striking is that the vast majority of these are comics that have no continuity. They’re either stand-alone stories (like those that EC would produce) or non-continuity stories with familiar characters. It seems to me that a lot of the theoretical tools that have been developed over time to study literature, or art, or film are not particularly pertinent to these works. I mean, you can apply them to single-page gag comics, but I’m not sure that they will be the most generative approach. I’m a big believer that expanding our scope of topics in comics studies is what will drive us to new insights.

PM: The very style of your writing and argumentation in this book is very peculiar, and it seems to push the envelope where academic discourse is concerned. I cannot shake the feeling however, seconded by things you’ve written and said over the years, that one can see this as a commentary about the current state of comics scholarship. Would that be a correct assessment?

BB: Very much. It’s funny, the biggest complaint I have about the reception of the book (and I’ve been extremely gratified by the feedback, don’t get me wrong) is that few people have seemed to address it as a meta-commentary on the state of the field. For some of that, I blame myself – in retrospect I feel like I should have been more straightforward about what I wanted to say instead of leaving it implicit. I didn’t really want to be didactic, but now recognize that I should have been. If you read Twelve-Cent Archie in conjunction with The Greatest Comic Book of All Time, which I co-authored last year with Ben Woo as a sort of introduction to the What Were Comics? project, you’ll note a certain reservation about close-reading as a method. But, of course, the Archie book is almost nothing but a close-reading, and Greatest concludes with one as well. I think some readers think I, or we in the latter case, are hypocrites but I think we’re offering a commentary on the field by doing the very thing that we’re advocating against!

PM: I’d like to ask two questions outside the purview of your book. I’m not sure if this is correct, but I think that Archie was only translated into French by a Canadian publisher, right? I would dare to say that Archie is largely unknown outside the United States (and Canada, I guess, and sorry for amalgamating the two in this) by more general audiences. But stories with Harvey Comics’s characters, Little Lulu, and a number of horror comics from the 1960s and 1970s have been translated profusely, not to mention, of course, Disney and superhero material. Of course, we would need to have more information here, but what do you think could be the reason it’s hard to “sell” Archie abroad?

BB: Yes, Archie does exist in French for the Franco-Canadian audience, but the series is almost completely unknown outside of English-speaking North America. Even in the United Kingdom it is pretty much unknown. I think that the series was particurlary American in its concerns when it launched, specifically with the depiction of the high school experience in the postwar era. A lot of the children’s comics that are most widely translated tend to be humourous adventures – Barks and Hergé – and they can be made a lot more international. There are exceptions, of course (Astérix is ridiculously French, but has translated well around the world), but for the most part Archie is just too particular. I was with some French comics scholars a few months ago and someone asked what I was working on and I said I had published this book and no one had paid any attention to it all because the material was completely unknown to them.

PM: Now, as of course, this book focuses on 1960s Archie comic books, before, as you say, “the end of the dominance of the comic books in the Archie mediascape” (203). But I would like to know what’s your take on the more contemporary relaunches of Archie, in which a certain mainstream continuity is instilled in the series (or a “sameness” in relation to Marvel, DC and Image comics, perhaps), from Mark Waid’s run to the just released series Your Pal Archie by Ty Templeton and Dan Parent, and a number of one-shots and recent experiences. Of course, it’s inevitable to ask about the Riverdale TV series as well… Are they bringing something new to the table, putting new life into these characters or, quite the contrary, erasing their unhip, “about-nothingness” and turning them into topicality clones?

BB: I have a very mixed relation to the current Archie product. As I write this I’m looking at framed Dan Parent sketches on my wall of Betty and Veronica, and I really like the work that he’s done. At the same time, I only watched the first episode of Riverdale because it just didn’t seem to speak to me at all (nor should it). I think I’ve been most interested in Adam Hughes’ work on Betty and Veronica. There is something genuinely creepy about it in how hyper-sexualized he has made these teenage girls. I look at it and think “this is just so wrong”. But that forces me to reflect on the fact that my preferred Archie artist is Harry Lucey, who was the artist who most sexualized Betty and Veronica in the 1960s. Indeed, I wonder if Lucey and Hughes aren’t so far apart, but are just separated by a half-century and a sexual revolution. So that has been helpful to make me re-examine my own biases. I know, though, that I won’t let my son read the Hughes book, nor watch Riverdale, and he is an enormous fan of Archie from the 1960 through the 1980s. I do worry about the company moving so far away from their core base of pre-teens with their recent moves.