This large format solo book by the French artist Hugues Micol is, for all ends and purposes, an account of the life of John Glanton, the infamous settler, soldier, Texas Ranger and bloody mercenary that contributed significantly to the overall idea of a violent, bloody and painful history in the birth of the United States. While not a book with a conventional pedagogical slant, Scalp could be thought anyway of as a tool for reconsidering the conceptual and even emotional schism between history and heritage. Delving mostly into the history of the American Southwest just during and after the Mexican-American war, and its aftermath (Glanton was born in 1819 and was killed in 1850) this a look into the pre-cowboy era that would be so romantically depicted throught the history of early American popular culture.

According to Micol himself, the origin of the book was born from a failed attempt in adaptating Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian, which includes a semi-fictional account of the horrific exploits of Glanton’s gang. Micol used his research and energy to try it from a different perspective, but there is much that is close to McCarthy’s book, such as the role of the distinctive Judge Holden, who plays a sort of a Virgilian role in the second half of the book.

To be honest, I am not certain how to divide the book. It is not organised in a classical linear manner, although a clear chronology is indicated. The focalization is always shifting, in fact, and the events are not always centered in Glanton’s own life, even though we do begin in his youth and follow him in his travels. From a strict narrative point of view, the book is rather confusing and allover the place, shifting levels and registers. It is only after the fact that one comes to terms with the books’s turbulent nature. At a given point, the narrative itself slips into a first-person account of one of the members of the gang, later revealed to be Samuel Chamberlain. He appears briefly at about a fourth of the book, as a witness to Glanton’s role in the Battle of Monterrey but seems to play an odd, secondary role. Then, midway of the book, he enters the gang thanks to Judge Holden. After Glanton’s horrific but (in Micol’s rendering) epic and iconic death at the hands of the revenging Quechan, the story becomes framed by Samuel’s own account, moving on to his own life, just before an epilogue centering on Glanton’s apparently and equally troublesome grandchild. While there is no extratextual mention to McCarthy’s novel nor to any other source, and despite the fact that within the diegesis Samuel never utters his own family name, he does mention his journal, My Confession: Recollections of a Rogue. This creates an intricate intertextual relationship, once again with McCarthy’s book and with Chamberlain’s journal, which was the source for the contemporary American novelist. Chamberlain’s journal seems to have been published for the very first time by Time/Life magazine in the form of multiple articles in the 1950s, and collected in book form in 1956 (another out of print, critical edition was made available in 1997). This will probably lead to a number of interesting academic unravellings about adaptation, fact and fiction, and so on.

One could call this an anti-western but then again, and repeating something I wrote before [albeit in Portuguese], it seems that the western is a genre that has been thriving with atypical and counter-examples for decades both in the U.S. and Europe where comics are concerned. Moreover, Micol has delved into this genre before, in collabortion with David B., with Terre de Feu, a dislocated Western in Patagonia. As a “malleable, targeted construct, a recodable universe subject to multiple forms of global domestication, innovation, and reconstruction” (see The Western in the Global South, edited by MaryEllen Higgins et al.), the Western is always already open for being refurbished with new characters, settings and political stances. While much of the violent tropes are present in Scalp, it it its sheer visuality that seems to open it up to new cycle.

Many of the depictions are that of horrible, sordid violent actions: cold-blooded murder of men, women and children, rape, scalping and disfiguring. But there’s a sort of carnivalesque approach to these actions. An artist such as Jack Jackson delved into this same historical context to create some of the most gut-wrenching, painful and raw scenes in comics form, but there is a sort of comical distance with the figuration that Micol uses in this project, as well with the distancing composition and the absence of a single narrative register.

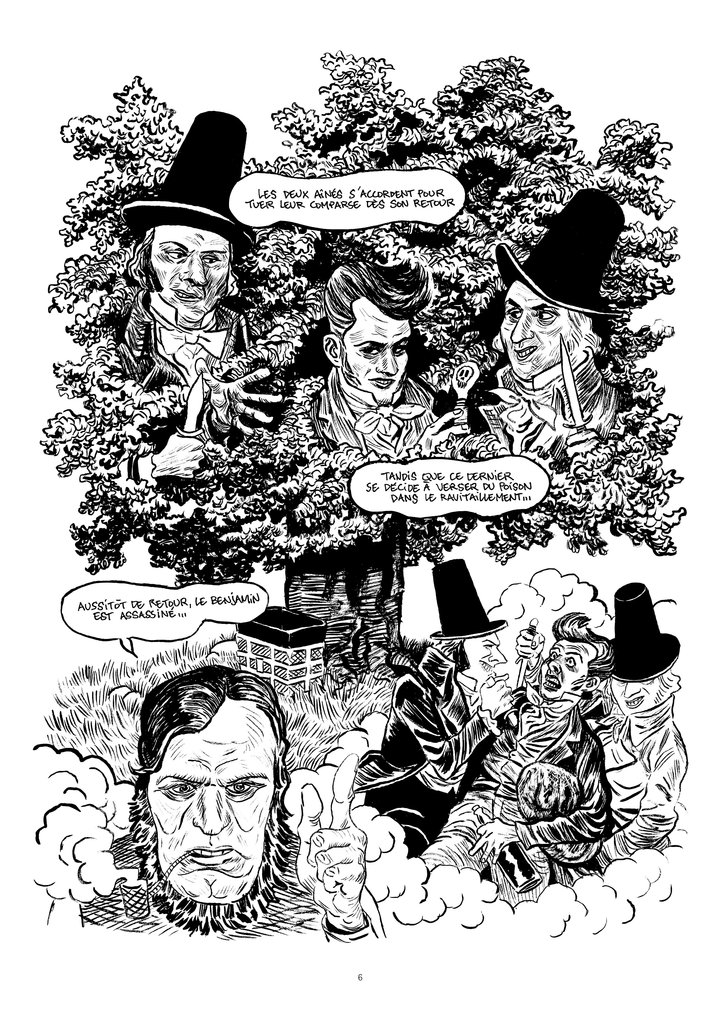

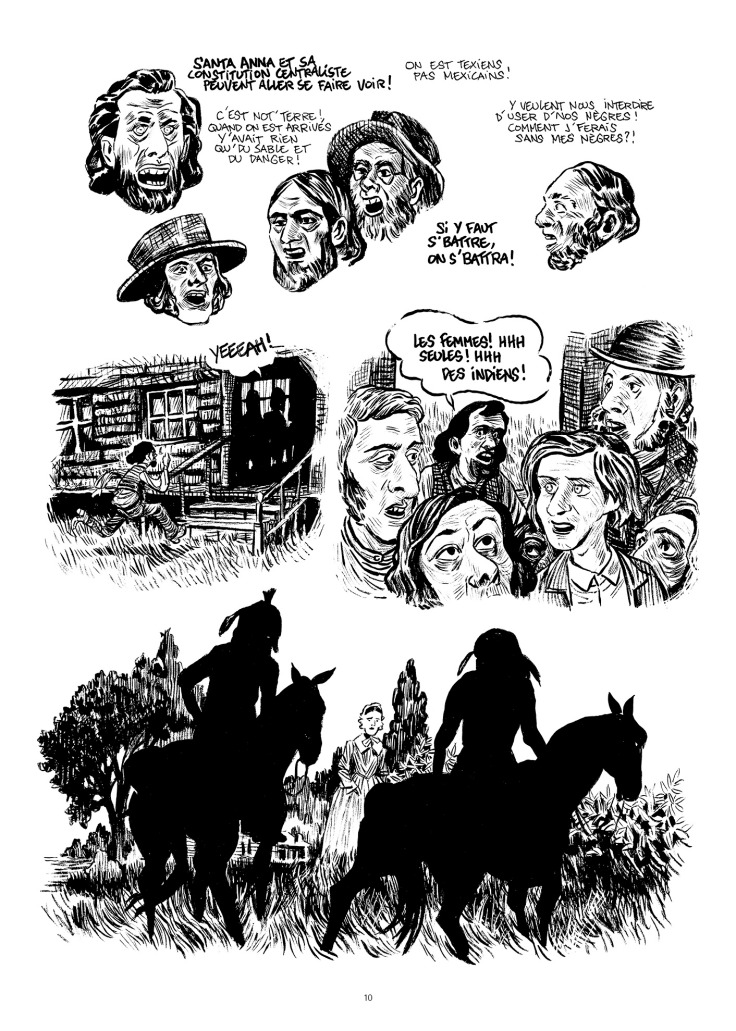

The author opts to draw the figures with slightly dispropornionate heads. While this may seem to connect to a comic visual tradition that harks back to the 18th century (see Alberto Milano’s article on the only issue of Studies in Graphic Narratives), its purpose in Scalp is rather more oneiric and monstrous (in the etymological sense of “admonish”). Micol never uses lines to separate the panels, and even though he does organize his pages according to some sort of clear-cut division or scenes, many of the pages dispense altogether with framing and just piles actions, bodies, mixtures foreground and background, and sometimes even creates unitary, iconic compositions from which the reader must sift each temporal signature and individual action, although the effect is purposefully that of turmoil and confusion. Glanton’s death, for instance, is represented by a sequence of powerful isolated drawings in their pages, which could be read almost like Posada posters.

The author actually quotes, in multiple interviews, Goya’s aquatints of Los Desastres de la Guerra as containing the impact he would like to reach. Arguably, these prints were created within the same time-frame of Glanton’s life, if in a completely distinct context, of course. Micol does indeed come close to the eeriness of the diluted blacks and the shadows from which some of the images seem to emerge, here and there, usually in the moments of stronger dramatism. Some other times his lines are also close to the lithographs, engravings and woodblock art that were common throughout the 19th century, also in the United States where illustrations of current affairs or fictional accounts of frontier life was concerned. Samuel Chamberlain himself created numerous drawings, paintings and prints of frontier and soldier life, with crude, naive figures, but I don’t believe there is much intertextuality there with Scalp.

Perhaps American readers will be able to read this book under the light of nation-building discourses, associating it with issues such as America’s Manifest Destiny, American Excepionalism, the historical tensions between Texian slaveholders and the impeding political frameworks brought about first by the Republic of Mexico and then the annexation to the Union, poverty and priviliges, racial inequality, and so on. These themes are not explored in a direct way but are part of the groundwork in which all actions take place and in which all personalities are molded.

Hughes Micol does not create a clear-cut psychological portrait of John Glanton. It’s not even a straightforward biography of the personage. It’s both a a plunge into incredibly ribald actions and a captivating study about the dark forces in the hearts of men, and how unleashing monsters in the name of purported “justice” and “rights” always backfires. But above all, Scalp is a visual tour de force with a many-faced phantasm: Glanton himself, of course, but also the popular culture construction of the “West” and the problematic heritage of violence and hatred as steps in the construction of modernity.

Deixe um comentário